The 'C' Word (Part 3)

Crafting curriculum with poverty and inequality in mind

In this three-part blog series, I explore what it means to shape an equitable curriculum; one that aims to meet the needs of those facing the greatest barriers to learning. Poverty and inequality.

Along the way, I’ll aim to draw on real-world examples from schools and research evidence. In this final blog, I consider how broader curriculum opportunities in schools can be further poverty-informed.

I remember those teachers that levelled curriculum opportunities for me.

Those who wanted to ensure that I had equitable access to learning.

I’ve shared this story before, at events and in other sources of my writing, but here is one that has stayed with me. I was in primary school when we went on a trip to the Jorvik Viking Centre in York. I don’t remember every detail, but I do remember being impressed by Viking history. It lit a spark. I’ve been back to Jorvik many times since. No doubt it played a role in leading me to teach History in schools too.

What stuck with me most, though, happened in the gift shop. As we spilled out of the exhibit, my classmates were eagerly spending pocket money on all manner of Viking themed tat; from horned helmets to plastic swords. My friend and I stood empty handed. No money, no souvenirs, no opportunity of getting involved in the post-trip excitement. But it didn’t seem to matter, we had enjoyed the visit.

Our Headteacher noticed.

He quietly came over, slipped each of us a £1 coin, and told us to buy ourselves something. I chose a Viking-themed ruler; the measuring kind, not the marauding kind.

On the bus home, I remember turning it over in my hands, reading the dates printed along the side, and feeling more involved in the day. I was already intrigued by the history, but what really stayed with me was that someone had seen something I might otherwise had missed. He had also done something about it. He had levelled learning and the curriculum encounter.

It wasn’t expensive, yet the experience and learning were invaluable for me.

If we want an equitable curriculum, we need more than good curriculum intentions and quality classroom teaching. We need moments like that; where someone notices unfairness, quietly intervenes, and levels the playing field. No child should leave an experience feeling like they have missed out simply because of what is or is not in their pocket. Especially those growing up in hardship.

But authentic equity isn’t always about grand or charitable gestures. Not every child arrives at the longship with a sword or shield. Equity means ensuring they still sail forward. Sometimes it’s about how we provide a wealth of care and attention to those with less.

The story so far…

So far in this series, I’ve shared that curriculum isn’t neutral. It never has been. It reflects power, values, and often unspoken assumptions about who and what matters. If educators are serious about equity, especially in contexts facing poverty and deep-rooted inequality, then tweaking curriculum documentation or delivery alone will not be enough.

Curriculum doesn’t just need refining. It needs reimagining.

This reimagining must include a critical look at the assumptions and misconceptions that underpin both what is taught and how it is delivered. It concerns the knowledge we hold as educators, our understanding of the communities we serve, and the living experiences learners bring (or are unable to bring) into the classroom. It is also about the knowledge made accessible to children and young people.

That knowledge cannot simply be a curated list of middle-class, elitist essentials handed down in the hope that it might somehow lift children out of poverty. Yes, curriculum should broaden horizons. Yes, it should cultivate awareness and understanding beyond the immediate. But we must interrogate how access to that knowledge is created and for whom.

Hardship can present real and present barriers to engaging with the kind of knowledge often assumed to be a ‘neutral’ baseline. It is neither fair nor equitable to pretend every child starts from the same place, with the same background knowledge or opportunity. To ignore this is to entrench disadvantage and inequality further.

As I explored in part 2, this is not about helping children and young people ‘fit’ into an existing system. It is about changing the system to serve them. Curriculum is more than content; it is a statement of value. It signals whose knowledge is centred, whose stories are told, and how we believe learning should unfold.

It is important to stress that I am not arguing against the value of knowledge or complex content here. If you want some commentary on the value of knowledge any it matters then read the likes to Rata (2015); Wheelahan (2010) or Young and Muller (2016). But, I am stressing that we need to carefully consider how accessible that knowledge is and how equitably it is served.

Equity demands that we ask: who is seen, who is heard, and who gets left behind?

This is especially vital when considering broader curriculum opportunity.

Beyond the gap

Gaps are prominent in education systems. Attainment gaps, vocabulary gaps, opportunity gaps… they arguably dominate language of policy and performance. I’ve written before about how a fixation on ‘the gap’ can oversimplify the deep-rooted structural inequalities that shape the lives of children, especially those facing long-term hardship and disadvantage. But as a starting point, gaps can serve some purpose: they signal that something is missing. They can prompt us to ask, missing for whom? and why?

Daniel Sobel (2018) reminds us that the attainment gap is not simply a number to be narrowed, but a symptom of wider social and economic realities. He urges educators to resist treating the gap as an abstract deficit and instead develop

“Rather than making the attainment gap into an abstract deficit that needs to be overcome, we need to look at the issue in context. The key is understanding the attainment gap in the context of a school embedded in a community, and producing community-focused solutions that make sense in that context.”

Sobel (2018) Narrowing the Attainment Gap

His call is not for less ambition, but for ambition that is grounded and recognises the lived (and living) experiences of children and families, and builds from there.

Of course, this is where good intentions can falter in a curriculum. Well-meaning enrichment activities, trips, performances, celebration days, can inadvertently amplify hardship when poverty is not part of the design process. A donation-based model or a policy of spreading payments over time may appear inclusive on the surface, but can sometimes miss the point. For families in entrenched financial hardship, the barrier is not just cost, it’s the unspoken assumptions about what is manageable and what is visible. When these assumptions go unchallenged or unrecognised, schools risk reinforcing the very inequities they are working to dismantle through curriculum,

This is one of the reasons why I have continued to champion initiatives like Poverty Proofing the School Day, developed by Children North East. These audits give schools the tools to examine their day-to-day practices through the lens of children growing up in poverty; identifying hidden costs, unintentional stigma, and moments of exclusion. In Brighton and Hove (amongst many other parts of the UK), this work has supported schools to think differently about how policies land in real families' lives, and to reimagine opportunity in ways that are genuinely accessible. Following work alongside Poverty Proofing teams, local services and organisations have produced resources to support all schools in navigating these complexities. The language around ‘easing the squeeze’ I find especially helpful in reducing some of the obvious stigma and issues that are presented by a language of disadvantage and poverty.

World Book Day is a good example here. While well-intentioned, this addition to curriculum can sometimes highlight the inequalities schools and charities seek to close. What is often framed as a fun tradition can quietly separate those who can from those who cannot; a celebration of reading that can inadvertently centre on what children wear, rather than what they read. It’s important to stress that I think World Book Day is a fantastic charity/initiative and one which can be an excellent addition to curriculum and learning in schools.

At Brambles Primary Academy, staff recognised this tension from feedback with families and children. They reimagined the day through a lens of equity, creativity, and community. Instead of asking families to provide costumes the school invested in plain white t-shirts for every pupil and supplying resources already available in school. Children were invited to design their own book-themed tops based on a text they had read, linking literacy and comprehension with artistic expression. The activity extended beyond school, as children took their t-shirts home to finish with family support. In doing so, reading became relational: a bridge between home and school, and a shared experience that didn't depend on disposable income. It is important to note here that children were given resources to take home to do this rather than make assumptions that every child could do so. It was also optional.

For just £475, every child had an equal opportunity to participate but the real return was in the atmosphere of joy, inclusion, and belonging that followed. Staff joined in, pupils created and performed raps inspired by their favourite stories, and the whole celebration was anchored around a wordless book that spoke volumes. Though a few families were initially hesitant about the shift away from costumes, many reached out afterwards to express gratitude; not just for removing financial pressure, but for giving them something purposeful and memorable to share with their children. You can read a case study about the activities here and read what children said about it.

(Source: Brambles Primary Academy)

It offers a reminder: when schools design curriculum opportunities with poverty in mind, they don’t lower expectations but they do raise participation.

This kind of poverty-informed practice doesn't dilute the curriculum, it strengthens it. When children are not worried about what they lack, they can be present with curiosity, with voice, with confidence. It is in these moments that I believe we can shift from mere talk of closing gaps. We can move from metrics to a curriculum that has outcomes anchored in belonging, dignity and a belief that school is for all, especially those facing hardship.

More than a mummy

(Source: Great North Museum visit; 2025)

At Pennyman Academy, as part of our SHINE funded Let Teachers SHINE project, we set out to explore how curriculum, beyond classroom content, could be made more equitable. While learning about Ancient Egypt, pupils expressed curiosity about whether there were any artefacts linked to this topic in our own region. When they discovered you could see an Egyptian mummy in Newcastle (Great North Museum) it caused much excitement! But this also sparked a broader exploration into local museums and the role they play in curriculum enrichment.

Initially, we assumed most children had visited museums in the North East and had a sense of what to expect. But we wanted to test this. Through class-based discussions and pupil surveys, we learned that while only 60% of pupils had visited a museum at some point, many had never been to Newcastle; even though it's only a short distance away. This challenged our assumptions and opened up deeper conversations about transport, access and experience.

Teachers worked in co-production with pupils to identify what children already knew, and didn’t know, about museums. Through sensitive questioning and research, pupils were invited to share any assumptions or misconceptions they held. We also explored with pupils what the term misconception means and why it is important for us to think about both as teachers and as learners. While we made it clear that we were not asking pupils to disclose personal or uncomfortable details about their experiences, children naturally drew on their known realities.

A clear message emerged: cost is a visible barrier to visiting museums. Despite most museums being free, pupils spoke candidly about the hidden costs; transport, packed lunches, and the social pressures of gift shops. Some shared how uncomfortable it feels when you are unable to buy something at the end of a trip, and you worry your parent might feel bad or embarrassed. Naturally, I found myself thinking back to my experiences as Year 6 and that memorable visit to Jorvik Viking centre.

Using funding from our research project, we co-planned a museum visit with pupils. This wasn’t just about learning more about Ancient Egypt in our core curriculum; it was about challenging misconceptions, removing barriers, and understanding what equitable access really looks like in practice. All of which supports the development, design and evaluation of curriculum too.

The experience led to a number of important insights, shared by pupils themselves:

Ensure water and food are freely available, so no child feels left out.

Where possible, avoid routing trips through gift shops or be upfront and thoughtful about how to navigate them.

Don’t assume all children have been to a museum or know what to expect on a trip, ask first.

Help pupils feel at ease; even exciting places can feel overwhelming or intimidating, especially if they are unfamiliar.

Recognise that this anxiety can affect families too; supporting parents and carers to feel confident matters.

Create calm, quiet spaces on the day, so children (and families) can rest or collect their thoughts.

Take photos using school devices so that all pupils can access them for future learning, rather than assuming everyone has their own phone or camera.

Provide keepsakes that help children talk about the trip at home, like the free postcards generously provided by museum staff on our visit, which gave every child a photograph of the site and information they could share with family.

This experience gave us a far more nuanced understanding of how to work with pupils, families, and museum partners to design inclusive, meaningful curriculum experiences. By listening closely to children, we moved beyond assumptions and towards practical, compassionate action that made learning richer and more equitable for all.

It was encouraging to see how deeply the principles of Poverty Proofing the School Day had been embedded within the practices of the museum, shaped by their ongoing work with Children North East (Poverty Proofing). Both subtle and explicit signs of this awareness were evident throughout our visit. From the outset, staff were thoughtful and proactive in helping us plan a trip that was equitable and inclusive for all pupils.

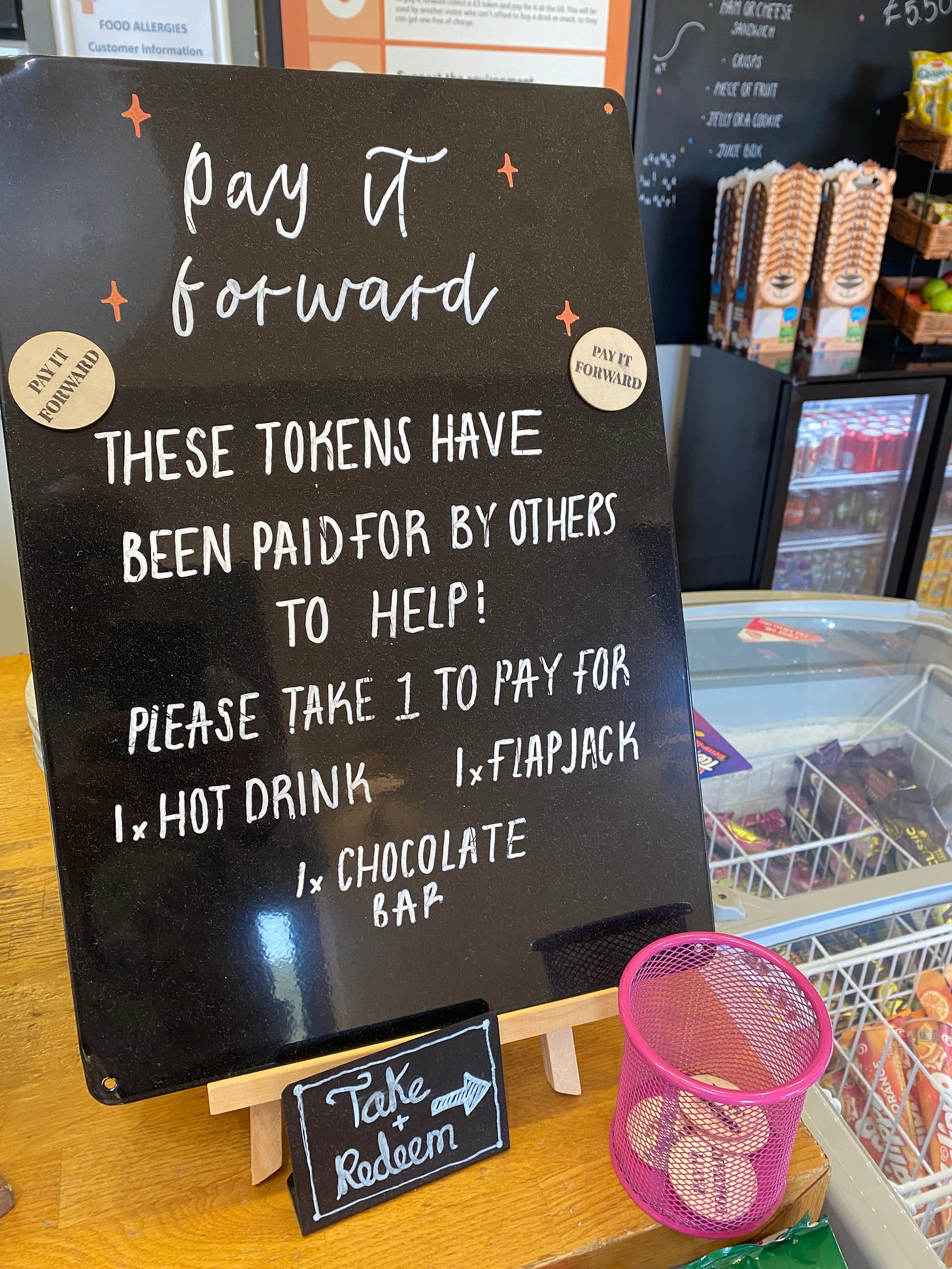

(Source: Great North Museum visit; 2025)

Every child received a free postcard as a keepsake, and importantly, there were no opportunities to buy items; removing any risk of children being singled out by what they could or could not afford. In the café, a quiet but powerful ‘pay-it-forward’ scheme allows visitors to make donations that cover the cost of refreshments for others, ensuring that families experiencing hardship can enjoy the space with dignity and without barriers. Our school group also entered through dedicated education visitor doors, bypassing the gift shop entirely; a small but meaningful choice that reinforced a commitment to inclusion.

For me, this curriculum opportunity illustrates that designing with poverty in mind is not just about being kind or caring. Though care remains essential. An ambitious curriculum should never be diluted in the name of inclusion; children from low-income backgrounds deserve challenge, depth, and the chance to engage with powerful knowledge just as much as, if not more than, those with a wealth of it. A well-crafted curriculum can ignite curiosity, open up abstract worlds, and offer concepts that poverty and hardship too often pushes out of reach. But ambition alone is not enough. We must ensure that what we offer is genuinely accessible, not in a tokenistic way, but in ways that dismantle stigma, that foster belonging, and that refuse to mark children out as 'other.'

Curriculum should not patronise or pity. Like the museum visit, these experiences are not just moments in time, they are cultural artefacts we help build with learners in schools and across other settings.

As curriculum architects, we are laying down memories and meaning. If we are not intentional, those moments can reinforce inequality. But if we are, if we design with equity in mind, they can be transformational.

Creating space

Creating equitable opportunities in the curriculum requires space to do so.

The Centre for Young Lives (CfYL) and the charity Mission 44 recently published a report with the argument that designing a curriculum that nurtures a love of learning and prepares children for the modern world requires addressing the current challenges of an overloaded and narrowly academic curriculum. Curriculum is only small part of the report as the ‘Everyone Included’ report deals more broadly with inclusive practices through and beyond curriculum.

According to the report authors, the intense focus on knowledge acquisition and exam success since 2010 has squeezed out time for deeper learning, critical thinking, problem-solving, and real-world relevance; key skills essential for learners today. CfYL and Mission 44 stress that inclusion must be embedded from the start; not bolted on as an afterthought. They argue that past decades of accountability-driven schooling have prioritised performance metrics over meaningful engagement, leaving many children feeling disconnected.

The report highlights that a reformed curriculum should broaden beyond traditional academic subjects to include technical, vocational, and enrichment opportunities, empowering children with greater voice and agency in their learning. This approach not only fosters motivation and ownership but is crucial to creating inclusive classroom experiences where every child can thrive. The upcoming government Curriculum and Assessment review recognition of inclusion is a positive step, but as cited in the report, the real transformation will come when curriculum design consistently reflects the diverse needs, interests, and realities of all learners, especially those historically marginalised.

The insights from CfYL reinforce a vital truth: designing a curriculum that truly serves all children means going beyond an overloaded academic checklist. It means creating space for deep learning, critical thinking, and skills that prepare young people for the complex realities of the modern world. Crucially, inclusion must be embedded from the very start of curriculum design, not treated as an add-on or afterthought. Without this, well-intentioned efforts risk reinforcing the very inequalities they seek to challenge, leaving some pupils feeling disengaged or ‘othered.’

When schools centre inclusion, equity, and community alongside ambition and challenge in curriculum, they can craft learning experiences that are meaningful and motivating for every pupil. This broader vision of curriculum holds power not just to close gaps in attainment, but to build richer, more equitable memories, identities, and futures for all I believe.

As curriculum architects, it is our responsibility to ensure that what we build in curriculum uplifts every learner, especially those facing poverty-related barriers to learning. Policy can clearly help to make this more possible.

The ‘c words’ in this final part of my blog series are challenge and compassion. Both help to ensure curriculum can remain ambitious not merely about knowledge, but about serving others.

Curriculum matters. But an equitable curriculum even more so.

Further Reading

Arthur et al. (2022) Teaching character education: What works?

Centre for Young Lives and Mission 44 (2025) Everyone included: Transforming our education system to be ambitious about inclusion. May 2025.

Chartered College of Teaching (n.d.) Leading Inclusive Schools. Available here

East London NHS Foundation Trust (2025) Understanding Lived Experience: Insights from Poverty Proofing.

Erickson (2002) Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Teaching Beyond the Facts

Harris, S. and Morley, K. (2025) Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools. Bloomsbury.

Harris (2025) Misconceptions and curiosity. SHINE.

Mazzoli Smith, L. and Todd, L. (2016) Poverty-proofing the School Day: Evaluation and Development Report. Newcastle University: Research Centre for Learning and Teaching.

Rata, E. (2015) A pedagogy of conceptual progression and the case for academic knowledge

Wheelahan (2010) Why Knowledge Matters in the Curriculum

Willingham (2009) Why Don’t Pupils Like School?

Young and Muller (2016) Curriculum and the Specialisation of Knowledge

Read more on creating equitable curriculum with poverty in mind here… 👇👇👇