Last week, I had to pull over my car while listening to a White House press briefing.

The briefing was in response to the tragic collision of a passenger jet and a U.S. Army helicopter over the Potomac River, the deadliest air crash in the country in decades. Sixty-seven lives were lost, leaving many families in mourning and disbelief.

As expected, the briefing began with solemnity. A moment of silence, an acknowledgement of the formal investigation to come, and a reassurance to the public about flight safety. I assume there are protocols for such occasions.

But then, the tone and narrative shifted.

President Donald Trump started to attribute the crash to diversity hiring practices, individuals with disabilities, and the Biden and Obama administrations.

One statement that stuck with me was this…

"We do not know what led to this crash, but we have some very strong opinions,"

"And I think we'll probably state those opinions now."

Rather than waiting for forensic analysis, Donald Trump suggested that the crash ‘may have’ been caused by diversity initiatives, criticising programmes that promote hiring qualified individuals from historically underrepresented groups. He’s also issued an order halting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives in government, arguing that ‘common sense’ hiring must be restored.

This moment serves as a harrowing case study in the pitfalls of assumption over assessment. Imagine being an air traffic controller involved in this tragedy or a grieving family member desperate for answers, only to hear sweeping opinions where there should be facts. Opinions over investigation are unlikely to bring about comfort, let alone factual evidence or investigative

The emphasis on assumption over assessment is not limited to politics; it manifests on the topic of educational inequality too.

The perils of poverty assumption

While I am no world leader, I do have experience in leadership within education and other sectors. I see this same pattern of assumption over assessment when it comes to addressing educational inequality. I’ve also been guilty of it sadly. I’ve written before about the myths and misconceptions that shape education policy and practice on tackling poverty. At times, dialogue about poverty and disadvantage rest on faulty assumptions rather than evidence-based analysis.

At Tees Valley Education, we don’t claim to be experts in solving inequality, but we do claim a commitment to working with others to grow our expertise, understanding and application of practice. Through research, collaboration, and an openness to learning, we refine our approach and in partnership with others. This commitment led to the creation of our PLACE initiative, developed with support from the Fair Education Alliance and Bloomberg. Through partnerships and rigorous enquiry, PLACE is helping us and other schools make informed, lasting change in the communities we serve.

We don’t claim to be the only multi-academy Trust or schools working in the ‘place based’ space. Our assessment is that it is needed and that we need to be curious about what this needs to look like in our context. Even if this means looking beyond what the ‘usual’ business of education and what schools have traditionally done.

Educational inequality cannot be solved by education alone. That’s not an assumption, it’s a conclusion drawn from years of research, thinking and practice.

Stating opinion…

It is easy to make assumptions about children and families facing poverty. I hear them often at education conferences:

"We need to raise the aspirations of those living in disadvantage."

"Our school serves one of the most deprived areas anywhere”

"Our high free school meal statistics show just how much poverty we have”

On a more personal level, I’ve heard school leaders use phrases such as…

"These parents are hard to reach."

"These kids don’t sit around a table for meals at home."

"Their parents don’t have aspirations, so the children don’t either."

Every time I hear these phrases, I have to bite my lip.

While there may be some truth behind this that can be supported by evidence, it’s the intent that I’m questioning. Every time we frame disadvantage or inequality this way, we risk doing what Trump did in his press conference - making miscalculated assumptions about the issue instead of calculated understanding.

Some of these statements may be well-intentioned. They reflect a belief that those with ‘less’ face greater barriers and significant inequalities. But too often, these ideas rest on the assumption that those with less simply need to work harder to achieve more. Even without meaning to, we can reinforce these myths.

And, of course, these are not limited to education…

(Source: Spectrum - Centre for Independent Living)

Rarely can they be backed by forensic analysis of the actual barriers children and families face. Like a world leader with opinions instead of facts, we can shape narratives to fit our own strategies rather than the actual needs of those that we work with.

Black box thinking

Like forensic analysts seeking to recover ‘black boxes’ from aircraft disasters, there is a complexity and a discomfort in searching what went wrong. The black box is a vital aviation device that records flight data and cockpit communications. It’s information is crucial for improving aviation safety by identifying what went wrong and forensically measuring the impact of incidents. This data enables authorities to implement safety measures that prevent future accidents and making flight safer for us all in the long term. At the heart of it is a belief that experts need to be obsessively curious about the problem, what went wrong and what needs to improve to ensure that better outcomes are achieved for all.

In my work with school leaders, I support them to identify real barriers to learning caused by poverty. But, this too is complex. Schools are under-resourced, leaders are time-poor, and many have not been trained to analyse the root causes of educational inequality.

What can happens is a kind of ‘cherry-picking’, adopting strategies from a latest pupil premium or teaching conference without adapting them to local needs. Real and lasting impact can come from precision, assessing the specific barriers pupils face and tailoring interventions accordingly.

Let me signpost a couple of examples where this works well.

TKAT ACE Mentoring

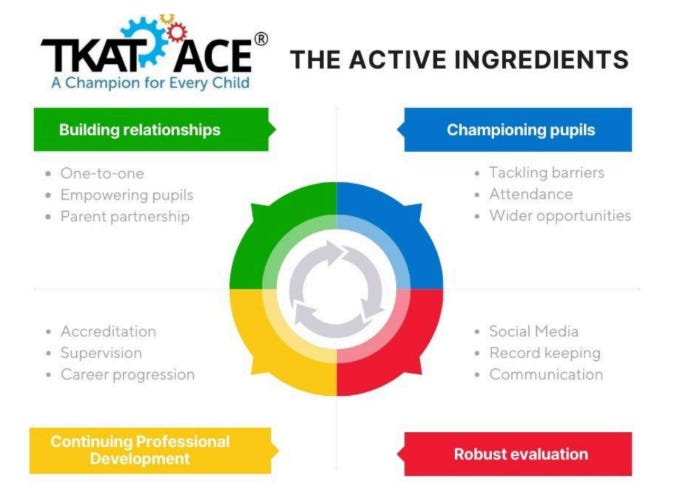

The Kemnal Academies Trust’s A Champion for Every Child (ACE) programme provides one-on-one mentoring for pupils that face aspects of disadvantage. Rather than assuming what these pupils need, ACE mentors work closely with pupils and families to identify challenges and co-develop solutions. It is built on four core drivers to support this analysis and implementation: the value of authentic relationships, championing pupils that face barriers, continuing professional development for the teams that deliver it and robust evaluation.

(Source: TKAT, ACE Mentoring)

This video showcases what the ACE project looks like in real-world terms and features the case study of a student and his family.

An external evaluation with ImpactEd found significant improvements in reading, maths, goal-setting, and school engagement. Find out more here.

Poverty Proofing the School Day

Poverty Proofing, developed by Children North East, is another example of assessment-driven intervention. It’s also rooted in listening to the actual voices of those that face inequalities, shifting conversations in schools and other places from mere beliefs to forensic understanding of barriers.

Through in-depth audits involving pupils, parents, and staff, schools identify financial barriers that exclude or stigmatise children, young people and families facing disadvantage. Where possible, Poverty Proofing researchers will speak to every staff member, family and young person to help with this understanding. This is because they recognise the value of these voices and that disadvantage is not limited to the mere labels of poverty, pupil premium or free-school meal proxies.

These audits have led to practical changes, such as eliminating hidden costs for trips and supplies, that ensure all children can fully participate in school life. Research has also shown that these approaches are having a vital impact in schools, particularly around whole school approaches to understanding barriers and improving outcomes for low-income pupils.

I’ve written here about the impact that Poverty Proofing has and the work that they do, especially through the voices of children, in not only understanding inequality but forming strategies to tackle it in partnership with schools and other organisations.

Poverty Proofing and the TKAT ACE mentoring approach feature in our forthcoming book Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools. The book also features case studies from other organisations and resources to support school-based leaders and educators in further developing these approaches in their own context. We’ve aimed to provide a book that is rooted in understanding and tackling inequality, rather than making assumptions that it is a quick-fix or one-size fits all approach in schools.

Why it matters

Marc Rowland, a leading voice on educational disadvantage, emphasises that ‘assessment, not assumption’ must guide our work in tackling inequality. If we misdiagnose the challenges pupils face, we implement ineffective solutions, leading to weaker outcomes. This can also result in a ‘supermarket sweep’ approach to intervention according to Rowland (2021)

Inequality impacts on pupils’ learning over time. It is a process, not an event, and affects every individual differently. But we are not powerless with this, and nor should we be indifferent.

We cannot allow our education system to be contaminated with an acceptance that disadvantaged pupils cannot attain well.

Marc Rowland: 2021

Whenever I talk about educational inequality, I will remember Trump’s press conference. It was a stark reminder of the dangers of assumption over assessment.

As educators, we are not addressing the nation from the White House. But we are speaking alongside communities, families, and children.

Our words, and the mindsets they reflect, have real consequences. We can and should resist the temptation to offer easy narratives and instead commit to the complexity of understanding.

The education sector needs logical, evidence-based thinking now more than ever. What it doesn’t need is hot air, uninformed opinions and tokenistic tributes to those facing hardship or tragedy.

Those experiencing educational inequality deserve more than assumptions.

If we genuinely want our efforts to understand and tackle inequality to take flight, then we have to be prepared to move into the uncomfortable, demanding and complex ‘black box’ thinking that must underpin it. Even if it does stand in stark contrast to how we see some influential leaders and thinkers operate.

That’s my assessment, not my assumption.

Further Links

Beeson et al (2024) Does tackling poverty related barriers to education improve school outcomes? Evidence from the North East of England.

Children North East: Homepage - Children North East

Harris (2024): Myths and misconceptions in tackling poverty

Rowland (2021) Addressing Educational Disadvantage in Schools and Colleges: The Essex Way

Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools: pre-ordering the resource

Tees Valley Education: Working with us and accessing our training support

TKAT ACE Mentoring: ImpactEd research evaluation report (2022)