Ten questions to ask about poverty and hardship in schools

And how Poverty Proofing© can help to answer them

I recently had the privilege of attending and speaking at an event championing ten years of Poverty Proofing©, which provided an excellent opportunity for reflection.

While the event highlighted the significant scale of the challenge, particularly in the North East, it also highlighted the unwavering commitment from multiple sectors and organisations. Together, they are demonstrating that, despite the difficulties, we can remain optimistic in addressing poverty and inequality on a large scale.

Here’s ten questions I’ve been asking about poverty in schools and other settings with thanks to Poverty Proofing© and other contributors at the event.

Are you listening?

In 2011, CNE gave 1,000 children cameras to capture poverty from their perspective, generating over 11,000 photographs. This research demonstrated how financial insecurity affects children’s school experiences, including meal access and participation in extracurricular activities.

The findings helped shape the Poverty Proofing© programme, with children describing feelings of exclusion when they were identified as being on Free School Meals (FSM), lacked school supplies, or were unable to attend school trips. Even today, Poverty Proofing audits endeavour to listen to the reality of all children, young people and families in communities/schools.

It’s a reminder, again, that the voices of children are paramount. But, it also reminds us that the ‘lived reality’ of those facing hardship, inequality and financial insecurity need to be at the heart of both understanding and tackling poverty, especially in education.

Can you spot your ‘well intentioned’ gorillas?

Children have reported feeling uncomfortable with how FSM can be managed in schools, particularly where eligibility was publicly known, such as being recorded in registers or marked by different exercise books.

Practices like these can amplify the stigma around receiving FSM, making children feel singled out. Offsite trips also caused embarrassment, as pupils on FSM were given paper lunch bags, further highlighting their disadvantaged status in front of their peers.

Many schools have already undertaken significant efforts to address these issues. However, even the most well-intentioned strategies can sometimes unintentionally exacerbate the inequalities experienced by those facing hardship and poverty. This is where external scrutiny becomes invaluable. By actively listening to the voices of those affected by inequality, we can uncover ‘blind spots’—areas of disadvantage that may have gone unnoticed within our teams, organisations, or communities.

I’m reminded here of Simmons and Chabris (1999) who conducted influential research on inattentional blindness, which refers to the phenomenon where individuals fail to perceive an unexpected stimulus in their visual field when they are focused on a specific task.

Schools and other organisations will carry out a plethora of well-intentioned ideas and interventions, some of which to address inequality. Without a ‘poverty informed’ lens on it (e.g. like Poverty Proofing©) we run the risk of dialing up the volume on hardship felt by others. Check out the gorilla test to see what I mean.

Are you providing food for thought?

In some research cases, Poverty Proofing© has experienced schools preventing pupils eligible for FSM from accessing their meal allowances during break times, forcing them to either stay hungry or miss out on socialising with friends in canteens. Needless to say, with the intent of trying to ensure that children eat at lunch time and make use of their FSM provision.

This policy can contribute to social isolation. In some schools, long queues, small portion sizes, or expensive food meant that some pupils were left without enough to eat, or forced to choose between food and drink, further entrenching inequality. Research further shows that FSM isn’t a great proxy for defining inequality in schools nor does it account for all those children/young people that may be experiencing disadvantage in broader ways.

Without going on a hierarchy of needs rant, children and young people that are hungry are not being set up to learn well. As I said in this feature with the Guardian, ‘if a child is hungry and not cared for it doesn’t matter whether you’re a bloody good teacher’

Follow Professor Greta DeFeyter’s work if you want to see some genuinely excellent work happening on this agenda.

(Source: A Day in the Life of a Secondary School Pupil in Relation to School Food (2024) (schoolfoodmatters.org)

What’s the cost of the ‘other’ stuff?

High costs associated with extracurricular activities such as ski trips, music lessons, or even local theme park visits can leave many children facing hardship further isolated.

Of course, many schools will provide these activities to help provide children, young people and families with ‘cultural capital’. But the very term itself is problematic. Read the likes of Ball et al (2002) to see how terms like this can oversimplify cultural diversity, reinforce elitism, and perpetuate deficit-based approaches to inequality.

Poverty Proofing© has found that exclusion is not just financial but social. Children have shared feelings of shame when they couldn’t afford essential items, like sports gear or spending money for trips. This has led to them opting out of even free activities due to the additional costs that came with them, reinforcing a cycle of exclusion.

It is important to offer these opportunities for all children. But, they need to be designed and provided in such a way that allows for equitable access.

World Book Day events are a notorious example. I was once accused of being a ‘spoil sport’ because I insisted on ensuring that students couldn’t dress up, knowing the impact that it can have on families from low-income backgrounds. I wasn’t for cancelling the event, but I did advocate reframing it with poverty in mind.

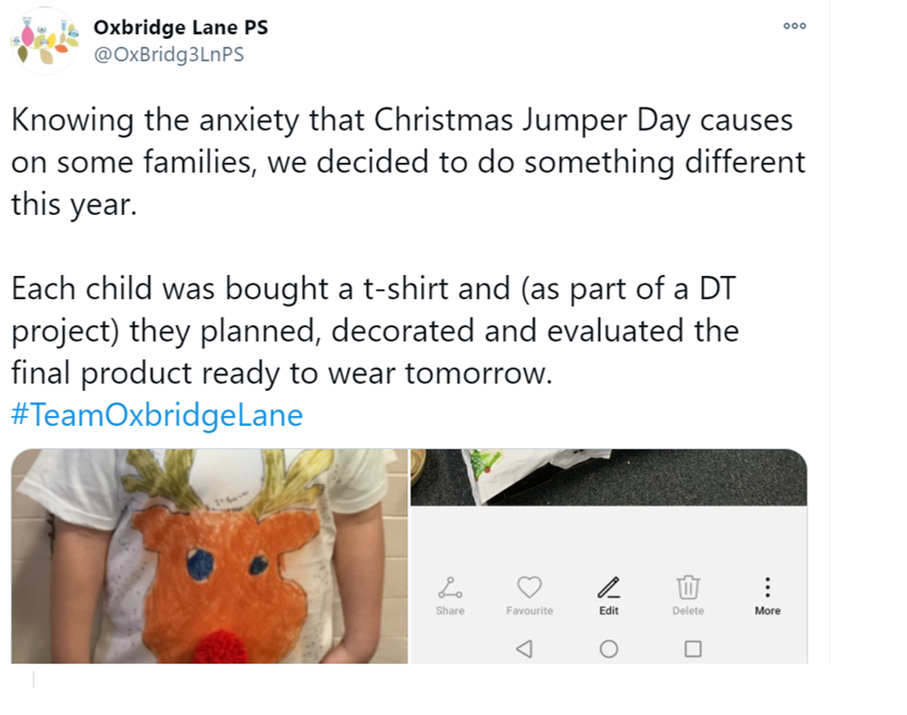

I’ve used the example from Oxbridge Lane Primary (Lingfield Trust) many times to share how events such as Christmas Jumper Days can also be reframed:

(Source: X @OxbridgeLane PS)

Are you considering the ‘home’ in homework?

Years ago, I remember being set a Maths homework task in Year 7 that involved going out into the local streets with a clipboard, pen, and paper to survey the types of cars—makes and models—that we could spot. Ironically, despite my current role as a researcher, I absolutely disliked this assignment. My parents didn’t drive, and I had very little knowledge of cars. Plus, I didn’t even own a clipboard! This made the homework task a real struggle, and I vividly recall the discomfort of presenting my findings in the Maths lesson.

Fast forward to the pandemic, we saw a surge in activities created to facilitate home learning. Teachers were improvising under pressure, and while well-intentioned, some tasks—like “go into your garden and record the sounds you hear”—were clearly inaccessible for students living in high-rise flats or with limited outdoor space. Homework assignments that aren’t designed with an awareness of poverty or disadvantage can inadvertently deepen the inequality that already exists within the curriculum.

Poverty Proofing© has helped to show children have sometimes faced difficulty for not completing homework due to a lack of materials at home. Some pupils, for instance, have reported being unable to make models for school projects (such as volcanoes or castles) because they couldn’t afford the necessary supplies. This created a further divide between pupils facing poverty-related barriers to learning and their peers, who had access to resources. These punitive measures can further disadvantage children for factors beyond their control and added pressure to already struggling families.

Again, I’m not proposing we ban homework in schools (but there’s definitely a blog in that…), but I am arguing that it needs to be designed and delivered with disadvantage in mind. We can’t assume every child is on an equitable footing with any in or out-of-classroom learning activities.

Have you temperature checked with others?

The Poverty Proofing© the School Day audit process involves focus groups and interviews with every pupil, staff member, and family, giving schools a comprehensive view of how poverty impacts school life. It now extends to a wide range of settings and organisations (e.g. healthcare, cultural organisations etc).

At the conference, there was a particularly thought-provoking sessions looking at the ways in which the National Trust is beginning to look more seriously at poverty-informed practice to ensure it is inclusive of all.

The audit aims to identify structural and cultural barriers that marginalise children, young people and families facing disadvantage. Each school receives a detailed report with recommendations, which often lead to cultural shifts, improved use of pupil premium funding, and practical changes to reduce the overall cost of the school day for all pupils.

Read more about the process here.

Do you have the ties that bind?

As an education leader, I’ve spent far too many hours enforcing uniform policies, often caught in fruitless battles with families over standards. While maintaining a sense of unity and expectation in schools is important, I now recognise with regret how misguided some of these efforts have been. I’m ashamed to admit that I, too, have contributed to the design and implementation of uniform policies that were supposed to raise attainment but, in reality, only deepened the struggles of those already facing inequality.

These policies, intended to promote cohesion, instead became barriers, highlighting the very disadvantages we should have been working to alleviate. From enforcing "they must be black leather shoes" to reprimanding over a "dog-eared tie," it’s clear that the uniform agenda in education is long overdue for a rethink.

(Source: Parents 'disgusted' by school uniform rules - BBC News)

Instead of focusing on superficial standards, we need to refocus on policies that truly support students and do not inadvertently place unnecessary pressure on those already facing disadvantage. It’s time we aligned uniform policies with the broader goals of inclusion, equity, and the wellbeing of all pupils.

While uniforms promote inclusivity, Poverty Proofing© research has found that the high cost of branded items, such as blazers or sports kits, create significant financial strain on families. Schools are encouraged to revise uniform policies to offer cheaper alternatives, such as sew-on or iron-on logos, and promote pre-loved uniform schemes. However, schools must handle these schemes carefully, as there is often a stigma attached to wearing second-hand clothes, which can discourage families from participating.

Despite some policy changes in this arena, there is still more work to do and I’d argue that schools are well placed at the local level to tackle this.

What is the ‘real’ cost of an education?

Research from Child Poverty Action Group (2023) has indicated that the annual price tag for going to secondary school is £1,755.97 per child and £864.87 for a primary school child. That’s £18,345.85 for children to go through all 14 years of school.

(Source: CPAG, 2023)

Poverty Proofing© has helped to identify many hidden costs that low-income families face, such as birthday cakes, teacher gifts, and school fundraising events. These costs, although seemingly small, created significant stress for families who could not afford them.

A multi-academy trust I work with has taken a thoughtful step by implementing a ‘no gifts’ policy for all teachers and support staff. While at first glance it might seem like an overreaction or a nod to cancel culture, the CEO’s rationale is rooted in empathy. The policy is designed to ensure that no staff member, particularly those on lower incomes such as early career teachers or teaching assistants, feels obligated to give gifts to colleagues or pupils, which can create financial strain. This move not only alleviates undue pressure on those already experiencing hardship but also sends a clear message to families. By openly addressing these financial concerns, the Trust signals its commitment to reducing burdens for both staff and families, fostering a culture of financial awareness and care.

It is important for schools to communicate clearly about all potential costs and to offer discreet support to ensure that no child is excluded from participating in school activities, reducing the financial burden on families.

Are you ‘ganging up’ on the issue?

In my family, we often remind ourselves to “gang up on the issue, not on each other.” This simple phrase becomes particularly meaningful when faced with stressors or tensions that could easily lead to blame. It encourages a shift in focus towards problem-solving and unity. We’ve carried this approach into leadership meetings at Tees Valley Education, not to separate accountability from ownership, but to foster collaborative solutions to complex challenges.

The concept of a "critical friend," as demonstrated by Poverty Proofing©, highlights the immense value of external perspectives in shaping poverty-informed strategies. In our role as a multi-academy trust, Tees Valley Education supports hundreds of schools and leadership teams across the UK on this vital issue, emphasising partnership and collaboration as the cornerstone of any meaningful response to poverty.

Schools are often seen as central in addressing community inequalities, and rightly so. They act as the beating heart of many communities. However, expecting schools to independently diagnose and solve the multi-layered problems of inequality overlooks a key truth: no single institution possesses all the expertise or resources required to tackle such systemic issues at scale. As I’ve argued before, educational inequality cannot be dismantled by education alone.

Collaboration with external organisations like Poverty Proofing© is crucial, especially for those early in their journey. Their insights help develop not just an awareness, but a strategic, actionable plan to reduce inequality, empowering schools to make more meaningful and sustainable changes.

Are you prepared to know more?

The work of Poverty Proofing© can be understandably challenging for some leaders and educational settings. Even the most well-meaning strategies can inadvertently perpetuate inequalities, making it uncomfortable to acknowledge when interventions, despite good intentions, are not having the desired effect. This realisation can be particularly difficult for those deeply committed to addressing disadvantage.

However, the Poverty Proofing© process often results in a profound cultural shift within schools. By actively engaging with pupils and families experiencing hardship, schools gain a deeper understanding of the systemic barriers affecting disadvantaged communities. This approach often leads to more strategic use of pupil premium funding, greater participation in school trips and extracurricular activities, and a more inclusive ethos overall. It highlights the need to consider poverty as more than just free school meals (FSM) eligibility, advocating for a community-wide commitment to inclusivity and equality.

There are ways to find out more…

I’m thrilled to announce that Poverty Proofing© will feature in our upcoming book with Bloomsbury, ‘Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools’. Alongside real-world case studies of its implementation, the book provides actionable insights for schools looking to apply Poverty Proofing© principles in their own contexts.

Recent research shows the effectiveness of this approach. A study conducted on primary schools in the North East of England, which had adopted Poverty Proofing, showed that pupils across all socioeconomic backgrounds benefitted from the removal of poverty-related barriers. Over two years, these schools saw a 5% improvement in attainment, a result observed in both FSM-eligible students and their peers, highlighting the universal benefits of Poverty Proofing.

Further links

Ball, S. J. (2013) The Education Debate. 2nd edn. Bristol: Policy Press.

Beeson, M., Wildman, J. et al. (2023) ‘The impact of Poverty Proofing on educational outcomes in North East England’, Journal of Education Policy, 38(1), pp. 22-45.

Children North East (2023) ‘Poverty Proofing: A Community Approach to Tackling Educational Inequality’. [online] Available at: https://www.children-ne.org.uk/poverty-proofing

CPAG, Children North East, NEU (2021) Turning the Page on Poverty.

Gorard, S. (2014) ‘The link between academies in England, pupil outcomes and local patterns of socio-economic segregation between schools’, Research Papers in Education, 29(3), pp. 276-297.

Harris, S. (2021) ‘Doorstep Disadvantage: Beyond the Pupil Premium’, SecEd

Holloway, D., et al. (2014) At what cost? Exposing the impact of poverty on school life. Children’s Commission on Poverty, The Children's Society.

Marmot, M., et al. (2021) Build Back Fairer: Covid-19, Marmot Review. The Health Foundation.

Montacute, R. and Cullinane, C. (2021) Learning in lockdown: Research brief. Sutton Trust.

Morley and Harris (2025) Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools. London: Bloomsbury.

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (2023) ‘Research Report: Impact of Poverty Proofing on Primary Schools’

Noden, P. and West, A. (2009) Attainment gaps between the most deprived and advantaged schools: A summary and discussion of research. Education Research Group at the London School of Economics, Sutton Trust.

Rowland, T. (2021) Addressing Educational Disadvantage in Schools and Colleges: The Essex Way. Unity Research School & Essex County Council.

SecEd Podcast (2020) Effective Pupil Premium Practice in Schools, December. [online] Available here

SecEd Podcast (2021) Tackling the Consequences of Poverty, June. [online] Available at: Available here

Sobel, D. (2018) Narrowing the Attainment Gap: A Handbook for Schools. London: Bloomsbury.

Turner, D. (2016) Secondary Curriculum and Assessment Design. London: Bloomsbury.