When you see or hear the word “goal,” what comes to mind?

For most, it might conjure images of a leather football hitting the back of a net amid the roar of an excited crowd. I won’t attempt a more forensic analogy here as somebody that has never been a fan of football (despite attempts!)

In education, ‘goal’ carries a different noise - not echoed in sporting stadiums but to the long term impact school leaders hope to achieve in communities.

A history of ‘goals’

The word "goal" itself has interesting roots.

Some commentators believe it first appeared in Middle English as "boundary" or "limit" in the 14th century, and various historians believe it evolved from the Old French ‘gaule,’ meaning ‘pole or stick’, which could represent a point to be reached or a line to cross.

It’s fitting, then, that goals in the context of personal or professional lives are also markers, often indicating where we hope to be or end up.

Recently, as part of my learning journey with the Fair Education Alliance’s Innovation Award (supported by Bloomberg), I joined fellow Award winners to reflect on how impact-driven goals can fuel systemic change in education.

Gathered on the nineteenth floor of a Canary Wharf skyscraper, we explored the intricacies of goal-setting for our unique innovation initiatives, finding plenty of inspiration, and challenge, to consider along the way.

Regular readers will know I’m using this blog to capture what some of this learning means for educators, especially in the context of PLACE (People, Learning and Community Engagement), an initiative by Tees Valley Education that works to address educational inequality.

Role of the goal in education

Impact goals in education differ significantly from typical school targets.

Rather than focusing on immediate results, impact goals aim for long-term changes that address deeper societal issues, like child poverty or educational inequality. At a recent seminar, we looked at how to define these goals and outcomes and were encouraged to frame our approach through the structure of What, Who, and How:

What: Articulate the desired change (e.g. improving educational access for children facing disadvantage in Teesside)

Who: Identify the people or groups who will benefit from this change (e.g. families, children, staff)

How: Determine the method by which this change will be achieved (e.g. through partnerships, policy influence, curriculum development)

The goalsetting approach emphasised the importance of planning with the end in mind—envisioning the final impact and aligning every project and activity with that larger mission. This avoids getting stuck in the trap of short-term actions that look productive but may not contribute to a bigger, lasting change.

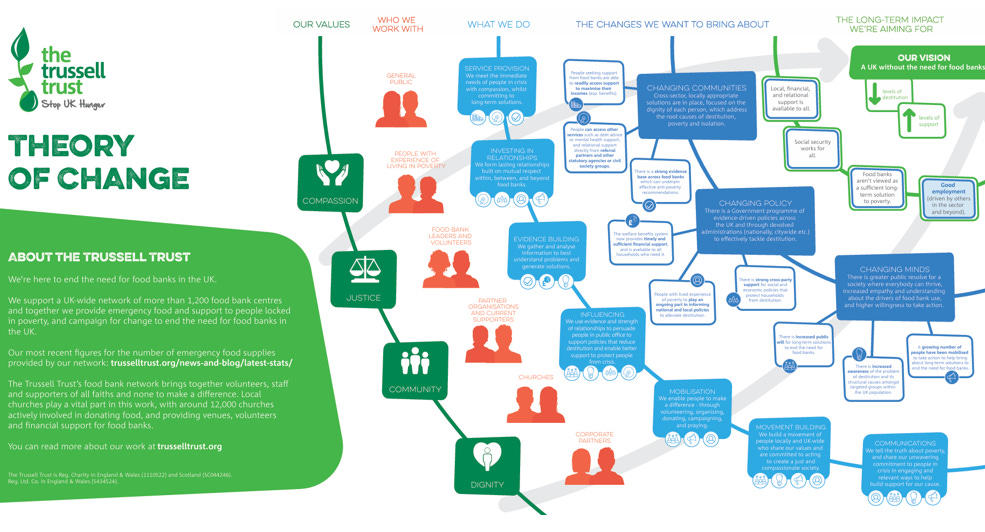

An example I found particularly helpful is the Theory of Change below from the the Trussell Trust. I think it’s helpful for clearly articulating the overarching vision and then codifying how aspects of this vision are met through goals, activities and the values that underpin the organisation. It’s also, I suspect, why Trussell continue to be a fantastic example of how to organise activity at scale in addressing food hunger (more on this here too)

(Source: What we do | Trussell)

Missing goals in education?

While goals can be transformative in education, they’re often not widely adopted. There are several reasons for this, backed by research and sector insights.

One challenge is the intense accountability focus in education, where schools are measured by quantifiable outcomes, such as exam scores, attendance rates, and inspection results. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), this results driven approach can tend to prioritise short-term metrics over broader, impact focused goals (OECD, 2018). It’s also one of the reasons why organisations such as the EEF dedicate so much time and resource to helping schools think more forensically about good implementation (EEF, 2024).

Another factor is the lack of training and frameworks that would help educators embrace goals aimed at systemic change. Qualifications such as the National Professional Qualification (NPQs) suite offer value to organisations, but I also think they can have a tendency to fall short when poorly implemented and/or when they fail to give adequate support to educators in better understanding implementation, goal setting and concepts such as theories of change (read the work here from Big Education to find out more)

Fair Education Alliance has highlighted that schools can lack exposure to strategic planning tools like Theory of Change (ToC), which are more common in social sectors than in education. This means that educators, although willing, are rarely supported with the methodologies necessary for mapping long-term pathways to impactful change (Fair Education Alliance, 2017). This was one of the core drivers for Tees Valley Education applying for the Innovation Award, because we knew it would drive our thinking and learning for long-term change.

Additionally, ‘compliance culture’ in education, as described by researcher Zhao (2016), can limit creativity and encourages a narrow view of success focused on exam based achievements rather than broader social outcomes (Zhao, 2016).

It’s one of the reasons why we insist on setting long-term targets and goals as part of performance management processes at Tees Valley Education, rather than just focusing on what can be achieved in one academic year only. I’ve written more here about how appraisal and performance management systems in schools can be more about professional dialogue and not just a mechanical target setting task.

Educators are often more comfortable setting immediate, tangible targets that satisfy external assessments rather than diving into ambitious, complex goals that might take years to produce fruit. In fairness to educators, this is sometimes driven by external policy and bodies more than it is internally in schools.

Goals in PLACE

At Tees Valley Education, our vision goes beyond orthodox educational targets.

Our PLACE (People, Learning and Community Engagement) initiative was forged to address inequality by engaging communities directly, fostering partnerships, and influencing policies that affect education.

We’ve outlined three pillars within PLACE that guide our goals based on what we believe to be the problem.

People: People are our biggest lever for change in our organisation and communities. Through professional development, we work with educators and leaders to address inequality effectively.

Place: Through hyperlocal understanding and projects, we work with children and communities to become agents of change within their ‘place’

Policy: We work with others to influence policy reforms to support educational equity, aiming to address issues like child poverty on a national scale.

Another ‘P’ which drives all of this and the goals behind it is ‘partnerships’. Expertise does not grow in silos and neither should our work to bring about long term change.

Our impact goals aren’t just educational—they’re about building opportunities that last. These goals align activities with a broader vision, so each project or programme we run contributes to tackling educational disadvantage in a sustained, holistic way.

We are still doing lots of work behind the scenes on this, so watch this space.

Big hairy audacious goals…

One of the guiding concepts we explore in our forthcoming book, Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools, is the idea of setting “Big Hairy Audacious Goals” (BHAGs), as coined by Jim Collins in Good to Great (Collins, 2001).

This concept is brought to life in a chapter by John Smith, Director of Partnerships at RGS Newcastle (his brilliant substack available here). John explores how school leaders can harness partnerships and develop frameworks for systemic change. By setting big, audacious goals, schools can target long-term transformations rather than mere incremental improvements (as an aside, the book contains a plethora of resources that can be downloaded for use in schools to help with this!)

According to John, the BHAG approach is crucial for impactful educational work, as it requires educators to think beyond their immediate influence and consider long-term, far-reaching objectives. This means breaking down each major goal into achievable steps while keeping the ultimate vision in sight.

One charity John highlights, DePaul UK, has a BHAG of ending youth homelessness. Schools partnering with DePaul (see their video below) align their smaller objectives with this larger mission, fostering meaningful partnerships that contribute to broader social change.

The Theory of Change (ToC) framework further helps leaders start with the end in mind and map out specific outcomes that lead to long-term objectives. ToC encourages educational institutions to frame their mission with measurable steps, making each action count toward a sustained impact on inequality and disadvantage.

(Source: FEA, Incubator Session; 2024)

Setting, then scoring

Impact goals provide a structured approach to ambitious change.

For our PLACE work at Tees Valley Education, this means moving from isolated activities to a comprehensive plan to address inequality through community engagement, professional training, and policy advocacy. Goals act as anchor points that drive our mission forward, keeping the larger vision of a more equitable society in focus. Complex to say the least!

Setting impact goals in education might be challenging, but the potential for transformative change makes it worth the effort.

By framing educational success through long-term, societal improvements rather than short-term metrics, we’re opening up new pathways for schools to become catalysts of social change and sources of hope for future generations.

In the process, we might score a few goals too…

Further links and reading

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2018). Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: [https://doi.org/10.1787/eag2018en](https://doi.org/10.1787/eag2018en).

Zhao, Y. (2016). Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon? Why China Has the Best (and Worst) Education System in the World. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fair Education Alliance (2017). Closing the Gap in Educational Inequality in the UK: 2017 Report. London: Fair Education Alliance.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

Harris, (2021) Appraisal: Can we talk about good professional dialogue? CPD development schools teachers; SecEd.

Education Policy Institute (EPI) (2020). Teacher shortages in England: Analysis and recommendations. London: EPI.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap... and Others Don’t. London: Random House.

Journal of Educational Change (2020). Broad goals and deep outcomes: How a systemic approach to impact transforms educational achievement and student wellbeing, Journal of Educational Change, 21(3), pp. 321–335.

Smith, J (2025) Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools (Harris & Morley); Bloomsbury, London. [PRE ORDER HERE]