Signs and signals

How the 'Batman Effect' might help you swing back into action this week

Happy New Year!

As the new year rolls in, many will attempt to renew themselves; signing up for gyms, buying blenders, and pretending they suddenly have a love for kale. Meanwhile, I’ve decided to take a different approach.

Instead of becoming a ‘new me’, I’m affirming the current one. I could aim to be healthier, fitter, or finally burn off the industrial quantity of chocolates I inhaled over Christmas… but instead, I’m starting my year with a proud, unapologetic affirmation of who I already am and what I’ve become. So, whilst 2025 me is so last year… I’m keeping me for this year too.

I’m a research geek. Even during the Christmas period, when many people are switching off, I find myself curling up with curious insights. Often these relate to poverty and inequality, but sometimes they wander into completely different worlds. Regular readers will know I’m also a comic book geek. So you can imagine my delight when those two worlds collided in a recently published study on what’s being called the Batman Effect.

This is actual research, rather than a mulled wine induced dream I had. A man dressed as Batman steps onto a crowded Milan metro. But what happened next is curious. Research from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Pagnini et al 2025) found that passengers instantly became more altruistic, far more likely to offer their seat to a pregnant woman than in a typical, routine situation. Curiously, nearly half of the people who behaved generously didn’t even realise Batman was there. According to the researchers, this ‘Batman Effect’ shows how unexpected interruptions to our routine can jolt us out of autopilot and reconnect us with what really matters; other people, our values, and a sense of shared humanity.

The numbers are also curious. Acts of altruism jumped from 37.66% in the normal condition to 67.21% when the caped crusader appeared. The researchers argue that this tiny moment of disruption created a flash of present-moment awareness; an opportunity enough to make people more sensitive to social cues and more likely to help. I’m not suggesting that this will always be the case, but the study indicates that small, surprising triggers can sometimes unlock significant prosocial behaviour.

If I wasn’t in the middle of writing a PhD on understanding and addressing child poverty, I’d be tempted to hop on a bus wearing a cape and claim it was all in the name of academic research. But what sparks my curiosity here is what this means for schools and charities. I cannot help wondering whether those of us working in education and charities, especially alongside communities facing hardship and poverty, could learn something from this caped-crusader ripple effect.

Could small, intentional interruptions help us break out of our own routines, notice more, and respond more attentively to the inequalities around us?

Signs of the times

Whenever I pick up a Batman comic, Gotham is almost always the same. It’s dark, gritty, rain-soaked, and permanently on the brink of collapse. The criminal underworld lurks in every alley, terrorising the very people Batman has sworn to protect. A part of me wonders, why don’t they just move to a nicer part of town? Or leave Gotham altogether?

But of course, in Gotham as in real life, it’s never that simple.

Over the last year, a plethora of reports drew an equally bleak picture across the communities many of us work alongside. Page after gritty looking page of data confirmed what many of us already feel every day; food insecurity rising, child poverty deepening, wellbeing spiralling beyond crisis levels. According to official figures released in 2025, 4.45 million children in the UK are now living in poverty; that’s a household income below 60% of the national median, around £22,500 a year. That’s 31% of all children. In some areas, the situation is even more severe. Research from the End Child Poverty Coalition and Loughborough University shows that more than half of all children in constituencies like Birmingham Ladywood, parts of Middlesbrough, Bradford, Liverpool and Leeds are growing up in poverty. The constituency with the highest level of child poverty is Birmingham Ladywood where 62% of children live in poverty. In a classroom of 30 children here, 18 would be living in poverty.

Research from Child of the North (2025) further adds to this graphic story. Children facing persistent disadvantage leave school nearly two years behind their peers. Only four in ten of the most disadvantaged pupils reach expected attainment by the end of school. School leaders report spending more time than ever dealing with the fallout of poverty such as food insecurity, attendance, behaviour, wellbeing and family crisis.

This isn’t a grim comic-book arc or a Dickensian exaggeration. It’s the lived and living reality for millions. Teachers, health workers and community practitioners see it every day. A November 2025 NEU poll found that 86% of teachers believe child poverty is limiting their pupils’ opportunities; with two in five say it’s doing so significantly. They describe hunger and malnourishment; children without clean uniforms or basic equipment; pupils ashamed to take part in lessons; families unable to afford trips or access outdoor spaces, books, quiet study areas, technology or even beds.

Nearly two-thirds (62%) of teachers said they regularly step beyond their usual teaching role to support pupils in poverty at least monthly; 43% do this weekly. They source food, clothes, learning resources, help with housing, washing machines, referrals and, like a hero, do whatever it takes.

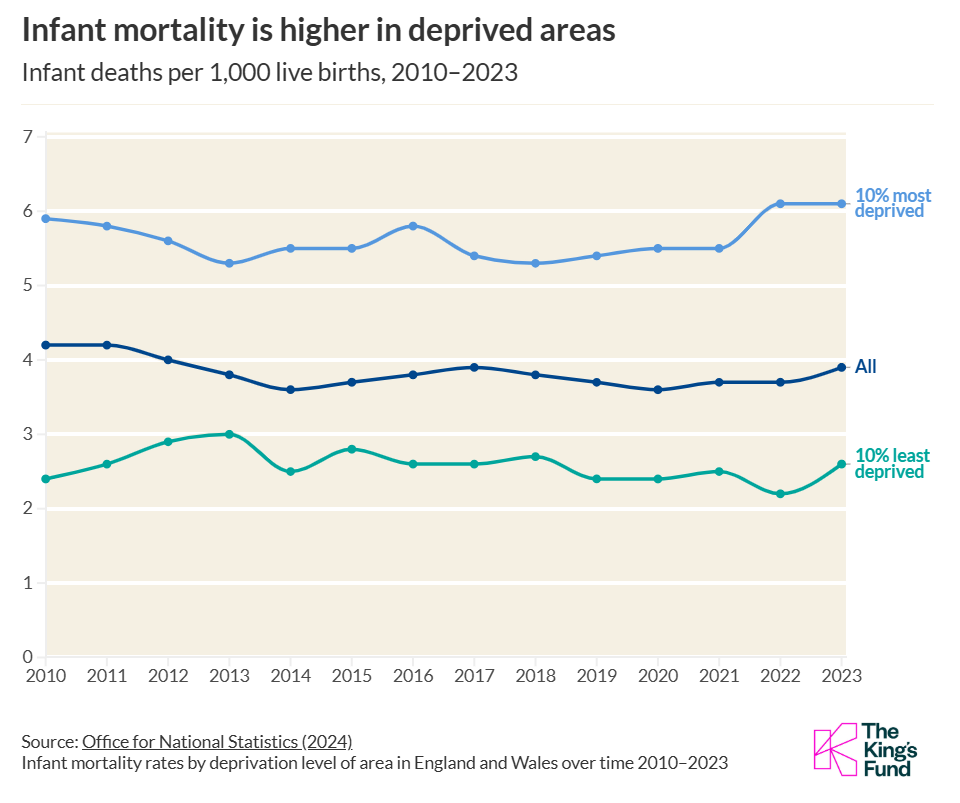

In comic book tragedy arc, the consequences are usually life-or-death. Research published by the King’s Fund last year shows that although child health has improved over the long term, the UK still lags internationally and stark inequalities persist. Infant mortality is more than twice as high in the most deprived areas. Children in these neighbourhoods are 1.7 times more likely to attend A&E. Hospital admissions for asthma are double the rate of the least deprived communities.

(Source: The King’s Fund, 2025)

There were some milestones to mark at the end of last year. The removal of the two-child benefit cap and the publication of a national strategy from government to tackle poverty. Yet, I believe a real and present danger is that this hardship has become a normal and expected narrative. When hardship is constant, it risks fading into the background, not because people don’t care, but because humans adapt. We can readily acclimatise to the very things that should shock or concern us. This is a form of survival instinct that allows us to live, sometimes long-term, with problems.

This is where the Batman Effect might offer more than a curiosity kick for geeks like me. Just as commuters on the Milan metro tuned out their surroundings until something unusual snapped them back into awareness, I believe that those working in schools and alongside communities in significant need can slip into a similar ‘survival-mode autopilot’.

“It’s been like this here for so long”

“These families are hard to reach and just don’t engage”

“These people lack aspiration and don’t see the value of getting out”

“Some children just never bring equipment.”

“These issues are out of our control”

Poverty becomes predictable and predictability becomes familiar. Familiar becomes hidden. Hidden can mean invisible. Autopilot suppresses the very things schools and communities need most to tackle inequality; curiosity, empathy, responsiveness and attentiveness. I’d argue that this matters especially in policy influencing and policy making circles too.

But, perhaps like with the people of Gotham, hope is not all lost.

Signals

The Batman study shows us that small, unexpected cues can unlock marked increases in empathetic behaviour; even when people don’t consciously notice the cue.

While poverty is a deeply sensitive topic, I believe that there is a need to communicate about it directly, openly and humanely. Reporting the scale of hardship through data and bleak literature is essential; we must keep poverty firmly on the radar of policymakers and the public. But I’m increasingly drawn to how we communicate poverty at the level of meaning; how we help communities translate statistics into lived and living realities, and how we spark a kind of “furious curiosity” that prevents poverty from fading into the background shadows of school or community life.

We cannot settle with simply describing or monitoring poverty. We should be working to disrupt it. It’s one of the reasons I support education leaders to think beyond monitoring attainment gaps. Closing gaps is vital, but it’s only one small part of the work. The deeper purpose is how we make poverty visible, discussable, actionable and never ‘just part of the routine’ in your setting.

Below, I’ve outlined a few forms of small but powerful signalling schools and settings can adopt. I want to stress that these should sit within a broader, thoughtful strategy for understanding and addressing poverty. They must be authentic, not tokenistic or worse, virtue poverty signalling.

Visible signs of lived experience

Not posters about poverty. Not stripped-back “poverty porn.” I mean humanising reminders, stories, voices, insights, that centre dignity and agency. Too often media coverage relies on intrusive portrayals of struggling families. If we want to communicate lived experience responsibly, it has to be done with care, consent, and equity. It should be shedding light on the challenge and not leaving room for interpretation of whether the person is really in need or not.

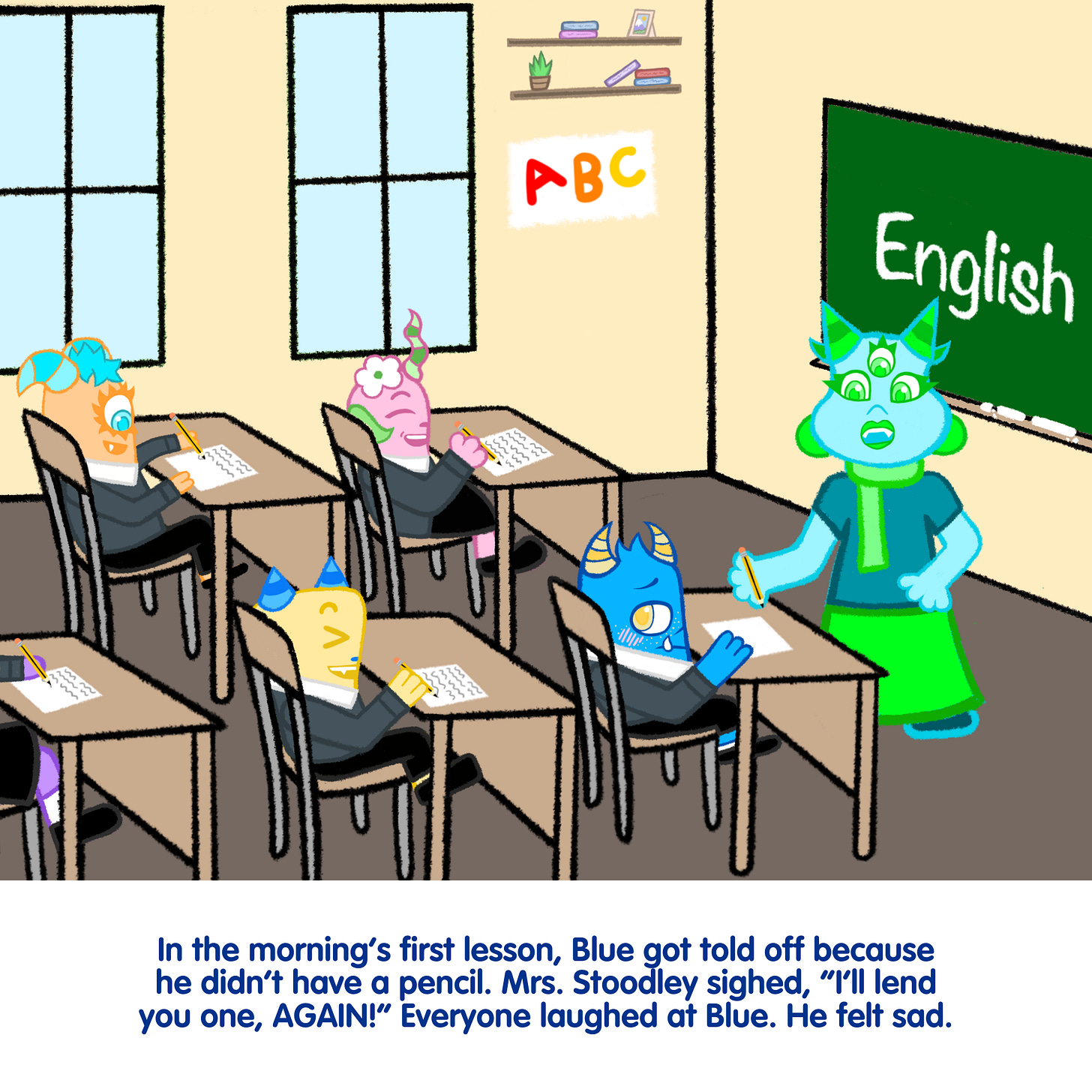

Children North East provided a brilliant example last year when they published a powerful, child-authored story on inequality that grounded data in lived experience. Blue’s Sad Day at School follows a young monster named Blue who lives with his family in poverty. Despite their hard work, Blue’s parents struggle to make ends meet. Throughout one normal day at school, Blue faces the challenges of living in poverty and starts to think about who could help him. Schools can do similar work, using student-led stories, community reels, case studies, photo narratives, or approaches from community organising.

(Source: Children North East)

My own PhD emerged from a provocation by my supervisor to stop asking what I thought poverty was, and instead ask what children thought. What questions they would pursue. What solutions they would imagine for their own contexts. That shift, from speaking about communities to speaking with them, is exactly the kind of visible reminder we need. More on how Professor Newbury-Birch works on these topics here.

Interruptions that spark reflection

Schools run on rituals and routines. Tiny adjustments to those rituals can be transformative. Yet we spend far more energy in the sector debating issues like silent corridors or display policies than we do creating deliberate routines for reflecting on disadvantage.

Intentional micro-interruptions could help teams stay curious rather than desensitised to the topics of child poverty and educational disadvantage:

Weekly ten-minute “What barriers might we be missing?” discussions

Spotlighting hidden costs in staff briefings

Checking assumptions about attendance patterns or homework

Embedding poverty-informed thinking into curriculum planning and professional development (more on this here)

Small changes can keep inequality from slipping into autopilot. They remind us that disadvantage isn’t an inevitability, it’s barriers that can be understood, challenged and redesigned. Consider the extent to which there is intentional or planned time in your leadership meetings and team discussions for authentic and direct dialogue about poverty. Without it, there is a chance it is becoming part of the background noise.

Prosocial priming

Just as Batman acted as a cultural cue for justice, schools can use symbols, values, and shared mantras to keep dignity, fairness, and compassion firmly in view. Yet, there is a danger that mission statements and values also become background noise or posters that, at best, look creative.

Think of this as poverty-informed priming; small reminders of who we’re really here for. Most schools already have core values, but how intentionally are those values applied to thinking about hardship and those with less? A value like compassion can be used to structure conversations about hunger. Dignity can shape decisions about uniform policies or payments for trips. Integrity can frame discussions about bias, assumptions, and invisible barriers. Especially for marginalised groups and the ways in which low-income amplifies levels of inequality for such groups.

Recently, I worked with Rainbow Education Multi Academy Trust in Merseyside. Their concept of the ‘rainbow’ sits at the heart of not only their identity but how they serve others; mission, culture, values. What struck me is that a rainbow doesn’t just appear. It requires conditions: the storm, the rain, the light. A rainbow is not the absence of struggle. It is the presence of light within it. Schools and many charities create that light every day, in breakfast clubs, quiet conversations, pastoral check-ins, tiny adjustments that restore a child’s sense of worth or a family’s sense of belonging.

If your values celebrate ‘thriving’, ‘flourishing’ or ‘achieving’ ask yourself, are our values explicitly rooted in serving those with less? That is where hope becomes visible. That is where values evolve from being simple slogans to signals of something greater.

Disrupting disadvantage

Poverty is not solved by capes and cowls, it requires significant system change. But daily disruption to the effects of disadvantage can be achieved through the quiet, intentional, everyday choices individuals make.

If Batman can double altruism on a metro train without speaking a word, imagine what deliberate micro-disruptions could do in a school or organisation committed to fairness, kindness and justice. Unlike the caped crusader, schools and charities don’t need to appear suddenly out of the shadows. They just need to notice.

To disrupt routine acknowledgment of poverty. To act with purpose and to put dignity at the heart of every decision. To ensure that those with less sit at the heart of the mission and work that they do. This requires a deep understanding of the need that exists. You can’t do this hiding in the shadows and not being alongside communities.

That is how we tackle inequality again this year, not with heroics, but with humanity. Your cowl and capes are not needed.

Fasinating application of the Batman Effect to poverty work. The point about autopilot desensitization explains why schools can have disadvantage data everywhere but still miss the actual kids struggling, the metric becomes wallpaper. I've noticed similar patterns in nonprofit spaces where everyone talks about 'serving vulnerable populations' but the daily rituals never actually disrupt routin assumptions. The Rainbow Trust framing is spot-on,light within struggle not absence of it.

Brilliant article and one that resonates with my experience in schools. I also love what you wrote about rainbows requiring challenging conditions *and* light in order to appear.