How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

And which bit do you eat first? The bit right in front of you.

Disclaimer for my vegan readers. I’m not advocating eating elephants. This old proverb reminds us that even the most complex and persistent problems are best tackled in stages. When it comes to inequality, the scale can feel daunting.

I had the privilege of visiting the House of Commons again this week, this time to support the launch of new research by the Food Foundation. Every time I walk through Parliament, I’m struck by the sheer volume of policy work unfolding; debates, roundtables, research launches, and strategic briefings, all aimed at tackling some of the biggest problems facing our country.

It’s a place where purposeful dialogue can happen, but also a place where silos still dominate. I could have walked into almost any room and found myself engaging with a topic relevant to my work on child poverty and inequality, because these issues cut across everything. Be it health, education, housing, or criminal justice… inequality can find a place in each discussion because it permeates all aspects of a child’s life and the living reality of millions of families right now.

And yet, food, something so basic and human, can remain on the periphery.

That’s why I was proud to stand with the Food Foundation for the launch of their third report in a critical series that examines food access and nutrition in the early years of childhood.

The Food Foundation are a national charity with a clear mission:

Our mission is changing food policy and business practice to ensure everyone, across the UK nations, can afford and access a healthy and sustainable diet.

We are policy entrepreneurs and use surprising and inventive ideas to catalyse and deliver fundamental change in the food system by building and synthesising strong evidence, shaping powerful coalitions, harnessing citizens’ voices and driving progress with impactful communications. We continually identify new opportunities for action, and trial new levers for change.

The Food Foundation

The event was a reminder that food isn’t merely about body fuel or personal tastes. It’s about equity, health and dignity. It also reminded me that food might be an elephant in the room for some of us committed to tackling poverty.

Hunger matters

One of the most compelling voices captured in the reports from the Food Foundation comes from Kathleen Kerridge, a mother, grandmother, and food ambassador who has lived through the complexities and failures of a benefits system.

Kathleen described how she fell into the ‘grey area’, earning just enough to be disqualified from free school meals, but not enough to reliably feed her children nutritious meals. Her words were painfully honest:

“What and how we feed our children is a minefield, and one of the most emotive topics a parent encounters. When parenting whilst facing food insecurity, trying to feed a child a healthy, well-balanced diet can seem daunting at best, and at worst, impossible. For me, it was the thing that nearly broke me entirely.”

Kathleen Kerridge: Food Ambassador; The Food Foundation

This is not an isolated story. Kathleen represents escalating numbers of families in this country who are being left behind by criteria that is too rigid and systems that are too slow to respond to real-life need. If you want to understand the scale of this in your communities, see this recent briefing from Child Poverty Action Group.

In a country as wealthy as the UK, this might shame us. But it should also give us an appetite for change.

Educating hunger

As an educator, I want to ensure that children and young people, regardless of background, have access to the high-quality learning and care they deserve. I believe passionately in the power of education to change lives.

But, to be blunt. We cannot simply teach a child out of hardship and hunger.

Of course we must invest in excellent teaching. In education circles, this is sometimes referred to as ‘quality first’ teaching. Research dictates that schools are a great lever for change in communities, and it also tells us that a quality teacher in front of a child really matters.

But, too often this rhetoric is lazily laced with the idea that all educational investment, resource and thinking should be directed at getting teachers to be better and, by proxy, we’ll demolish disadvantage on the way.

The lived and living reality of millions of children and families facing hardship tells otherwise. Of course schools matter. But as I said in this Guardian article with reporter Anna Fazackerley:

If a child is hungry and not cared for it doesn’t matter whether you’re a bloody good teacher.

When a child arrives at school too hungry to think, learning becomes a luxury. When parents are skipping meals to feed their children, their capacity might be spent on survival as opposed engagement with their child’s learning. When families are trapped in a cycle of low pay, precarious work, and rising food costs, educational outcomes suffer, not because schools aren’t trying, but because the system is fundamentally uneven and inequitable.

Collaboration with organisations such as the Food Foundation is stirring in me an unsatisfiable hunger for talk and action in education beyond silos. Education of children does not work in a vacuum. Food justice is education justice, which also happens to feed social justice

Hunger, as a basic human necessity, undermines so much of what we are trying to achieve across multiple sectors and communities.

Addressing hunger early

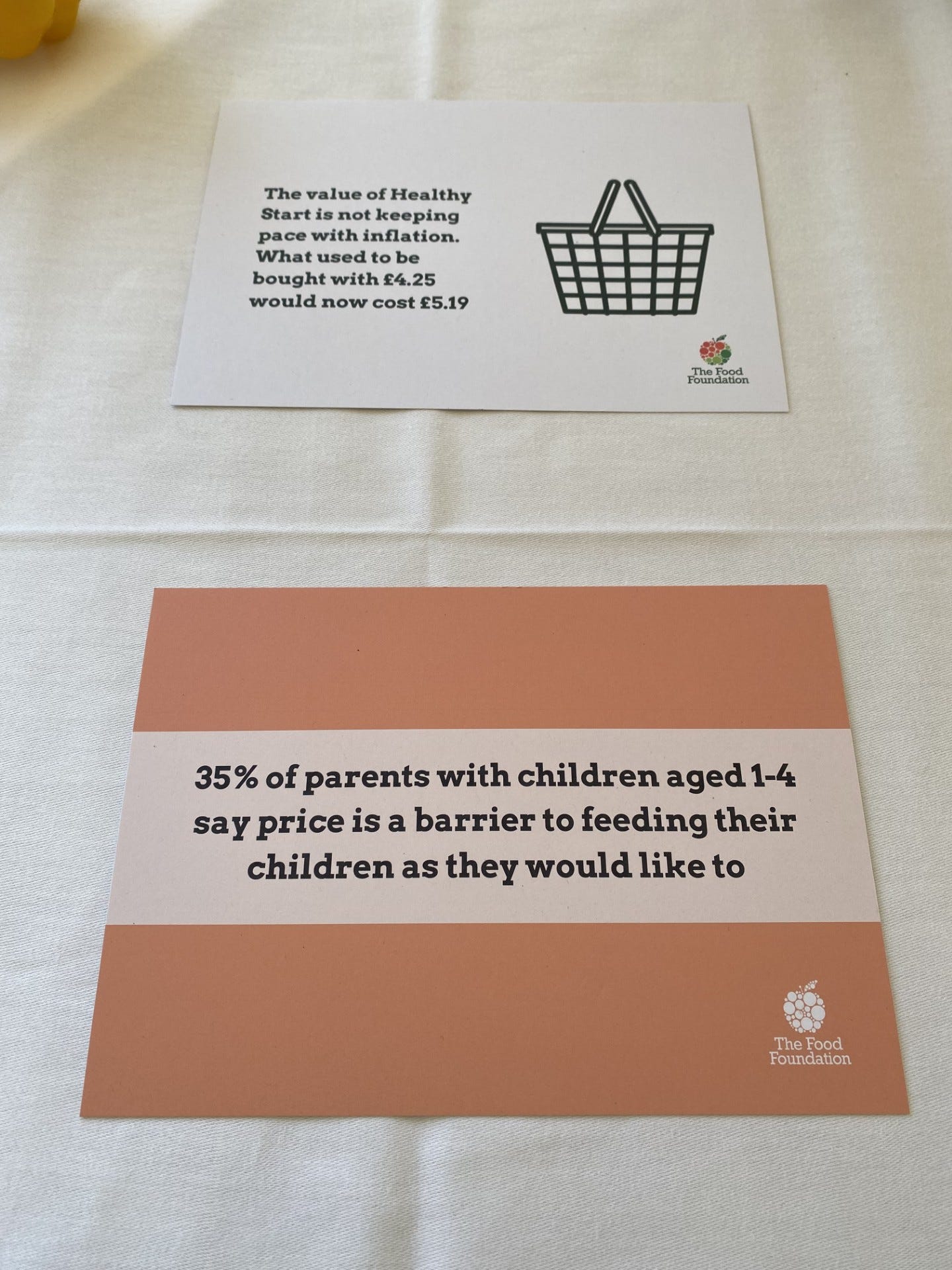

According to the latest research report from the Food Foundation, a chronic lack of investment and attention on the early years is resulting in widespread health and diet inequalities, creating unnecessary barriers to providing nutritious food.

(Source: The Food Foundation; 2025)

The report does not simply offer breadcrumbs of the problems. It is full with practical, evidence-based recommendations that could shift how we think about food policy in the early years

Here are the headline recommendations (but I’d recommend you reading the report in full to get a clearer idea of what is recommended in practical terms)

Improve the affordability of healthy diets and strengthen nutritional safety nets, especially for low-income families.

Tighten regulations on the composition and marketing of baby foods and formula milk.

Support early years settings to deliver healthy, nutritious meals for every child.

Invest in local services and protections to provide wraparound support for families facing food insecurity.

Shift incentives across the food system, so that health and nutrition are built into the food economy, not treated as afterthoughts.

These are not radical provocations or suggestions, they make good sense. And the economic case is clear, investing in healthy nutrition in the early years reduces future spending on healthcare, improves educational outcomes, and supports long-term economic productivity.

Everybody benefits by ensuring that food is front and centre of plans to better understand and tackle inequalities. It has to be part of the set menu of innovations and ideas being adopted to better tackle inequalities in policy and communities.

Appetites for agency

I’ve seen first-hand the power of what’s possible when schools and communities work together to take action. At Dormanstown Primary Academy, part of Tees Valley Education, extraordinary staff, families, and children have collaborated with local community groups and organisations to co-develop a school-led farm shop.

(Source: Dormanstown Primary Academy; TVEd)

This isn’t a food bank. It’s a dignified, collaborative response to food insecurity; rooted in people, learning, and an understanding of place.

Children help to lead it. They support with stock, pricing, and even marketing. They engage with local organisations and food suppliers. They learn the value of food and the importance of equity. Most importantly, families are offered choice and dignity, not simply a handout.

This initiative, supported by generous external funding, shows what is possible when we stop seeing children and families as passive recipients and start seeing them as agents of change in place.

Of course, what we truly want is a system that satisfies hunger and addresses inequality. But, system change is supported through agency.

The youth-led organisation, Bite Back, has launched an inspiring campaign that challenges fast food corporations’ advertising dominance in urban spaces. Their message is clear. Young people are tired of being aggressively targeted with unhealthy options. They want change, and they’re not waiting for permission to demand it.

(Source: Bite Back)

Schools at the table.

Early on in my teaching career, I recall a senior leader saying to me “you just stick to teaching the kids and the pastoral teams will worry about the other stuff”

The leader had a clear mental model of what education is and this informed how they thought it should be delivered. It didn’t fit my idea of what education is and the transformative capacity of education more broadly.

Schools are often put into the silo of thinking about education in the currency of pupil outcomes, attendance data and one-word judgements. But the reality is that educators are already on the frontline of understanding and tackling hardship. Schools see it in lunchboxes, in attendance data, in the quiet fatigue of the child who hasn’t eaten since yesterday. And so these educators understand that education must not be understood only as a vehicle for knowledge and exam outcomes.

I also believe we should stop any talk of schools being the ‘beating heart’ of communities. Schools can not be expected to solve everything in silos, but they should be part of the conversation. Educators and all other adults working in school contexts have unique insights. Many understand what families are experiencing. They can, and must, help shape the policy landscape that affects the children we serve. Schools are a vital organ, but let’s not hierarchically put them above the other vital organs that exist in the form of charities, families and other lifelines.

But, this isn’t just about food or support. It’s about what kind of country we want to be.

On a more personal level, it leaves us with a question about our own mental models on the topics of food and equity. Do we believe healthy food is a right for every child, or a privilege for the few?

If you work in education, public health, or government, I urge you: read the reports published by the Food Foundation. But go further. Prepare the table for others to digest the vital themes and issues on the plate here. Share the reports and thinking. Talk to your colleagues. Engage your local councillors and MPs. Invite parents, families and young people into these discussions too.

And if you’re in a position to do so, fund these efforts.

We need a majority to see food not just as a nutritional issue, but as a human rights issue. One that links hunger with housing, with income, with education, and with justice.

Supporting the work of the Food Foundation gives me some hope. It’s also why Tees Valley Education will continue to champion the work and support their campaigns. It helps to show that it is not too late to build a better food system; but we need the care, commitment and the collaboration to do so.

How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

And which bit do you eat first? The bit right in front of you.

But let’s make sure that the elephant is in front of the hungry to begin with.

Further Links.

If this has provided you with food for thought. Support it with action too.

🍎 Read the latest report from the Food Foundation

🍏 Share this blog with others

🍉 Get involved with the work of the Food Foundation

🍓 Contact me directly if you want to support/invest in our work with communities in the Tees Valley and through the work of our academies