To borrow a well-known phrase **it happens 💩

I remember once delivering what I thought was an inspiring assembly. The theme was about making a difference, and I spoke about how positive actions can create ripples of change that impact communities. As a newly appointed school leader, I was keen to make an impression as Year 10 students looked at me in that cold school hall.

As part of our ongoing pupil voice initiative, designed to gauge the impact of assemblies and collective worship, it had become routine to invite a few students at the end to share their reflections. After delivering what I believed was a powerful and thought-provoking message, I approached a group to ask what they had taken from the morning gathering.

One student thoughtfully said it made them reflect on the importance of kindness and helping others. Before I could respond, another chipped in:

“Yeah, about that. Sir, your flies are undone. You might want to check that before doing assemblies in front of Year 10.”

Needless to say, it was not the learning outcome I’d hoped for them. But I had earned something valuable that day, not just about leadership and delivering assemblies, but about dressing myself properly in the morning!

Mistakes happen. And they can provide a good opportunity for learning. But, learning is sometimes uncomfortable, messy and complex. This is especially hardened for those facing hardship. Learning is too often more complex for those with less.

It’s messy…

I want to offer some caveats before exploring how to tackle misconceptions and the topic of ‘messy learning’. In this piece, I’m not simply referring to spotting and correcting errors. This builds on recent reflections I’ve shared about curriculum design, particularly considering poverty and inequality.

Poverty does not automatically mean every pupil from a low-income background will struggle with learning new knowledge. It is vital to challenge that assumption. Nor am I suggesting diluting knowledge so that learning is always easy. New learning is often challenging, and complex concepts are embedded in curricula worldwide. Learning is often messy and regardless of your background or income status.

However, as I’ve argued in my recent series of blogs on curriculum, accessibility and opportunity are critical. It can be the difference between accessing and understanding this content.

I also want to touch on a prickly but relevant area; neurology and cognitive science. A growing body of evidence suggests that poverty and hardship can affect the learning brain. I’ve explored this alongside others in greater depth in Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools. If you want to understand more about this then I’d recommend a read of Blair and Raver (2016); Hackman and Farah (2009); Jensen (2009) McLaughlin et al (2014) and others I’ve mentioned in the further links section at the end.

Again, it’s important to emphasise that poverty does not mean that every child facing hardship will be neurologically impacted, and poverty alone cannot be said to cause these effects outright. The evidence indicates a multitude of interacting factors. Poverty, and hardship more generally, is multifaceted: hunger, food insecurity, poor housing, health challenges exacerbated by economic stress can all influence a child’s opportunity to learn over time.

Current studies appear to share a consensus that the influences of poverty on brain development come from an accumulation of factors and the length of exposure to these social environments (Jensen 2009; McLaughlin et al 2014; Wagmiller, 2015). This deserves a blog of its own. But for now, here is a summative starting point:

Learning is inherently complex.

Poverty and hardship makes it even more so.

From limited access to resources, to hunger, to the day-to-day stresses of hardship; learning becomes more of an ask for those with less.

So, it follows that as educators must consider how to make learning more accessible. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the learning is made simple or more relevant, but making the opportunity to engage with it more achievable and the learning less messy. One of the ways we can achieve this is through predicting and responding to what students will struggle with in the form of misconceptions.

‘Messy learning’ from the frontline

Let me take you back to that assembly I mentioned a moment ago. With the wisdom of hindsight, and frankly, a quick check of my trousers… I could have spared myself some embarrassment. That check is now part of my pre-flight keynote routine. But please don’t look out for it!

Hindsight is a glorious, and at times, deeply humbling learning tool.

As feminist novelist and poet Grace Paley wrote,

Hindsight, usually looked down upon, is probably as valuable as foresight, since it does include a few facts.

Grace Paley: Later the Same Day, Harmondsworth, 1985

As a newly qualified teacher (back in the NQT days before the ECT rebrand), hindsight quickly became a surprisingly loyal companion to me. I can now look back on some of those early lessons and fully understand why they didn’t quite land. But at the time, my personal and professional learning was messy. I didn’t yet have the knowledge or experience to draw from; to help me see in advance how things might go wrong, or how a more thoughtful design could make things land better.

Let me take you back to one memorable lesson on Just War Theory.

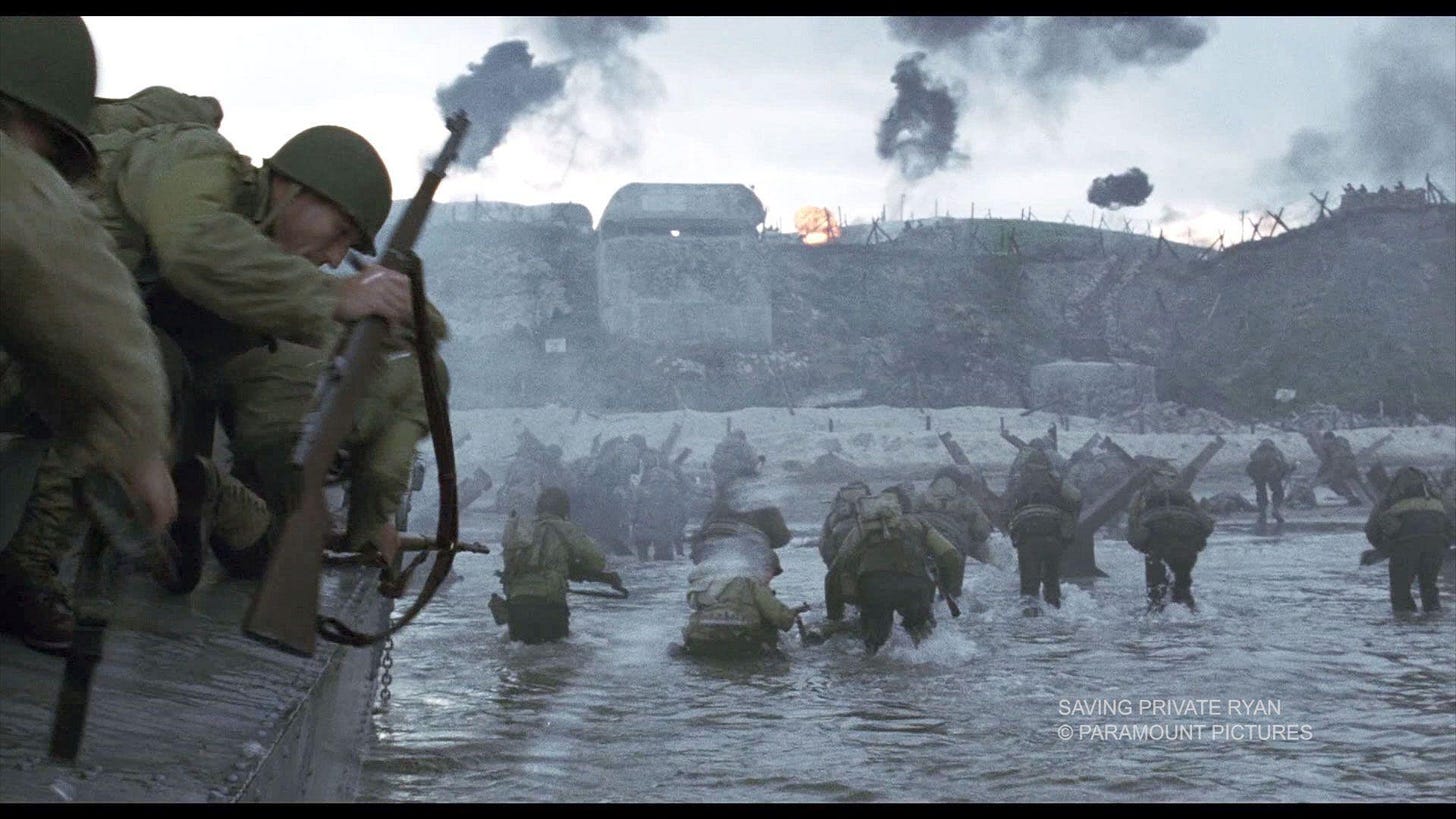

It was an observed lesson, so I had pulled out all the stops. Pupils entered to the opening sequence of Saving Private Ryan; full surround sound, cinematic mayhem, the lot. Normandy landings. Spielberg. Shaky camera. Bangs. Crashes. The then Head of Teaching and Learning nodded enthusiastically as the students were visibly wowed. A ticker tape I’d painstakingly edited across the screen asked them to copy the lesson title and list three positives and three negatives about war.

I believed I was winning in the war against GCSE student apathy on a Friday afternoon…

(Source: Saving Private Ryan; Paramount Pictures)

I got an Outstanding grade for the lesson (it was a thing at the time!). Armed with a clipboard and smile, my lesson observer left with a view that I had conquered in my role as an educator.

But my students learned almost nothing.

They were engaged; who wouldn’t be by a blockbuster war movie on a Friday afternoon? But did they deepen their understanding of Just War Theory? Did they grapple with the ethics of conflict, or examine the complexity of human decisions in political or historical contexts? No.

Later in-class assessments made that painfully clear. Hindsight, once again, tapped me on the shoulder… this time holding their books as evidence.

I had entertained. I had not taught.

Even worse, I hadn’t thought about the two pupil premium eligible students in that class who had close family serving in the military. I hadn’t considered what they might already know or feel. I hadn’t considered what any of the class did or didn’t bring with them, culturally or emotionally. I was too focused on the ‘wow’ factor, and not nearly focused enough on the why, what or how I would help students to access it.

That whole unit surfaced misconceptions: about what war is, why it happens, who it impacts, and how it shapes politics, people and place. Hindsight helped me to see it did not work. But knowledge and experience has helped me to see that forethought would have been a greater ally to me that day.

Daniel Willingham (2013) writes:

“Students learn more when their teachers know the content, and when they can anticipate student misconceptions… low-achieving students are especially vulnerable when teachers lack knowledge.”

This quote continues to stick with me. Hindsight showed me the gaps I didn’t know to look for back then, because I did not yet have the experience or knowledge to anticipate what pupils might misunderstand or struggle with. Like a battlefield, I’ve had flashbacks to that lesson and unit more than once.

What I have since learned about serving students facing hardship is that it is never enough to reflect after the lesson. A post-mortem of a lesson is only ever going to tell you what went wrong and what was a struggle. This is important but we need to think beforehand about what might go wrong, especially when teaching students with less. Less prior knowledge. Less resource. Less opportunity.

Pre-mortems and poverty

There are no single silver bullets or tools for making learning equitable and accessible for all. But, there are principles, processes and practices that do make incisions.

One of the tools I continue to use as an educator is that of a ‘pre mortem’. It’s a helpful tool (but more so a habit) to build into lesson design. Rather than just post-mortem the damage, why not plan for what will go wrong? It can be an excellent way of considering what learning looks like and how inaccessible it is for those facing poverty-related barriers to learning - and what to do about it. Needless to say, it has roots and use in other sectors too, so I’d encourage you to consider how to use it in other contexts also.

For the tool to work most effectively, it is vital that the barriers to learning faced by students are based on an assessment of the issue not an assumption. I’ve written more about this here if you are unfamiliar with where to start on this.

Identify common misconceptions in a lesson/topic

Begin by anticipating where students might go wrong, not due to a lack of ability, but because of prior gaps, different life experiences, or missed foundations. For learners experiencing poverty, misconceptions may be rooted in limited access to prior learning opportunities, vocabulary gaps, or simply different lived experiences. Mapping these misconceptions in advance helps you to teach proactively, not reactively. It also means that curriculum and content is being considered with the living realities of students in mind, rather than an assumption that they all have the same starting point or should do.

I have written more here on how these misconceptions can be further assessed or understood in co-production with teachers and students too.

Mould the ‘messy’ and incorrect

Instead of waiting to be surprised by student misunderstandings, write down the likely ‘wrong’ answers you expect to hear. Mould what you expect to go wrong and how this might manifest in the learning process.

This step is about empathy, thinking like your learners. If a child has never had the language exposure at home or struggles with abstract reasoning due to stress or unmet needs, how might they interpret your question?

These drafts offer a window into the internal logic a student might be applying, even if it’s inaccurate. Don’t assume an incorrect answer is apathy or unbotheredness!

Draft prompts you would give to correct these

Next, plan or script your response. What questions, cues, or representations might help nudge a student toward deeper understanding? These prompts should be low-stakes, curiosity-driven, and supportive.

For students facing disadvantage, thoughtful prompting can build confidence, repair misconceptions, and provide the relational safety needed to re-engage with learning. Over many years I have learned some stock phrases and comments that I wish I’d known earlier in my career.

Here’s a couple of examples from me…

Form pre-mortem habits

This is your chance to imagine the learning going wrong before it happens and so you can plan to prevent it.

A pre-mortem isn’t about deficit thinking; it’s about anticipation and precision. As you walk through this process, hold in mind the names and faces of children for whom learning is most complex. Those with less.

Picture the child who comes to school without breakfast, not by choice, but by circumstance. The student who stays quiet, not because they aren’t thinking, but because they’re unsure whether their thinking is ‘right enough’ to share. The one who hides confusion behind humour, hoping it distracts from what they don’t yet understand. These are the learners who most need us to plan with equity and empathy at the forefront.

My pal, and education guru, Jon Tait explores this beautifully through the idea of ‘cheat seats’ in the classroom: practical tools that reduce cognitive overload and offer scaffolding without stigma. Layered alongside this pre-mortem approach, such strategies can transform uncertainty into opportunity for every child.

Pre-mortem opportunities

The concept of pre-mortem planning extends beyond curriculum and classrooms.

In fact, I’d argue that schools and organisations should apply this approach to the planning of events and initiatives aimed at supporting children and families from low-income backgrounds. Take World Book Day, for example. I’ve previously written about how one of our schools within Tees Valley Education has consciously reframed the day through the lens of inequality; ensuring that every child can access and enjoy the opportunity without feeling excluded due to cost or circumstance.

As one student powerfully put it to me:

“To better tackle poverty and other issues like it, you’ve got to know what it’s like to walk in the shoes of others.”

I am writing a PhD in these topics, and I genuinely couldn’t have put it better myself!

I encourage leaders to use a pre-mortem lens when planning events: think about the intended impact of the day/event, then work backwards to identify the specific barriers that might prevent some students or families from fully participating. It’s a simple but useful way to plan with intent.

The team behind Poverty Proofing the School Day have developed some free-to-access practical resources to help schools do exactly this; ensuring that inclusion and dignity are never reserved for the few. You can also read about the principles and processes that they use in a dedicated chapter in our book Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools.

Further Links

Blair & Raver: Poverty, stress and brain development: New directions for prevention and intervention, Academic Paediatrics, 2016.

Hackman & Farah: Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in Cognitive Science, January 2009: https://bit.ly/3FMvT6X

Harris: Poverty on the brain: Five strategies to counter the impact of disadvantage in the classroom cognitive function ; SecEd

Harris & Morley: Tackling Poverty and Disadvantage in Schools; Bloomsbury, 2025.

Jensen: Teaching with Poverty in Mind: What being poor does to kids’ brains and what schools can do about it, ASCD, 2009.

McLaughlin, Sheridan & Lambert: Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience, Neuroscience and Biobehavorial Reviews (47), 2014.